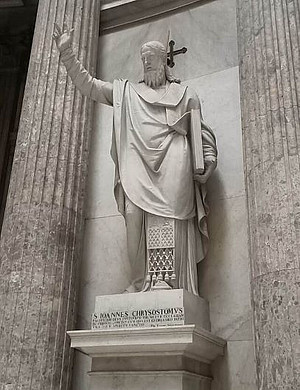

John of Chrysostomus

Life

Born to a Roman military family in Antioch of Syria, he had access to a privileged Greek education. He studied with the famous rhetorician Libanius. After completing his studies 367, he attached himself to the group led by Bishop Meletius of Antioch, which included Diodore of Tarsus, Flavian (later bishop of Constantinople), and J.’s friend, Theodore of Mopsuestia. Here he became familiar with the historical and grammatical focus of the exegesis that came to be associated with the “Antiochene School.” Around 372, J. headed for a life of seclusion in the mountains where he was under the direction of an old Syrian monk for four years. Finally, in 378, J. returned to Antioch, coordinate with the re-institution of Melitius after the death of Emperor Valens. J. served as a reader and became a priest in 386 once Flavian became bishop upon M.’s death. Under the will of Emperor Arcadius, J. was ordained bishop of the capital city, Constantinople, in 398. He reformed the life of the clergy, urging simplicity and generosity to the poor. J. worked to establish hospitals and refuges for strangers and gave away much for the disadvantaged in the city. He cared, too, for monks, virgins, widows, and deaconesses and paid special attention to the liturgical functions of the church in Constantinople. His successes in caring for the people were mitigated, however, by his political ineptitude. Theophilus of Alexandria brought charges against J. after he sheltered a number of monks accused of Origenism who had fled from Egypt (the “Tall Brothers”). Theophilus convened the “Synod of the Oak,” a meeting of 49 bishops, which ruled against J. and which persuaded the imperial court to side with its decision. J.’s exile was short-lived, though. He was summoned to return the day after because the empress perceived some sign from heaven that he should be re-instated. J. continued to defend the Origenists, however, and was deposed and exiled for good in 404. During his time away he composed many letters, staying in touch with constituents in Constantinople and offering spiritual advice. He died in 407.

Work

He has left behind the largest corpus of writings of any Greek-speaking church father. In addition to over 700 sermons, he also has over 240 letters (1-17 to deaconess Olympias), and 17 treatises.

1. Exegetical: OT (Gen, 2 series, Psa, Is 6, Job) NT (90 hom on Mt, 88 on Jn, 55 on Acts, and on Paul). His exegesis is straightforward, intended to elucidate difficulties (grammar, syntax, linguistic meaning or historical sequence) in the text. Although he avoids allegory, he is not blind to Scripture’s deeper meaning. In general, this further level of meaning is a matter of a moral lesson. This moralism is, however, tempered by the sense of awe before God’s disclosure of himself in Scripture.

Series of homilies against the Jews, on the Statues, on the unknowability of God (against Eunomianism), and catechetical sermons. Treatise On Priesthood (fence of his flight from ordination by bishop Meletios, takes the unusual form of a dialogue with his friend Basil, whom he left in the lurch to face Meletios alone). Surpassed contemporaries in purity and elegance of style.

Theology

J. did not focus on theological and dogmatic issues because he believed these would only confuse his congregation and would not give them the certainty of the moral, practical purposes of Scripture. He did not gloss over problems in the Bible, but concentrated on the literal meaning of the text, drawing moral lessons from them through the process of theoria, or contemplation. Several sermons evidence a strong faction of Jews in Antioch against whom J. directed several sermons. These have caused him to be labeled an anti-Semite. J. exhibited concern that his parishioners understand the liturgy, and he devoted many sermons to the topic. He recommended that one’s entire life be turned into a liturgy by following Christ’s commandments exemplifying his love to the world and thereby influencing the surrounding unbelieving community.

He was given the appellation “Chrysostom” (“golden mouth”) in the 5th/6th century because of the exemplary oratorical skills present in his works. He stands as one of the “three hierarchs” of the Orthodox Church. In addition, J. was much studied by two important Protestant theologians, John Calvin and John Wesley.