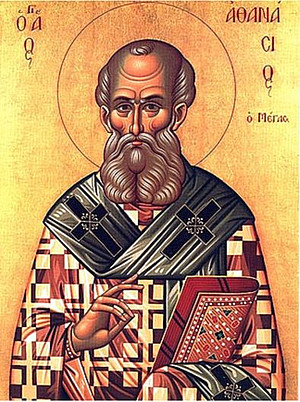

Athanasius

Athanasius entered church life young, serving as secretary to Bishop Alexander of Alexandria, even at the Council of Nicea in 325. According to the wishes of Alexander, Athanasius became bishop upon the latter’s death in 328. In 335 he was condemned for political disobedience and exiled to Trier, starting a long succession of exiles from Alexandria, though he was able to return this time in 337. Two years later he was banished again, fleeing to Rome and remaining in the West until 346. He was condemned by Constantius and nearly arrested in 356, but he fled to the desert where monks sheltered and hid him. Finally, in 363, he returned to Alexandria for good

The Arian controversy loomed large in A.’s literary activity. He added many letters to his dogmatic works, while also penning the influential biography of Anthony. De incarnatione—a very famous piece—argued that human salvation is accomplished by the incarnation of the Logos. Through the three Orationes contra Arianos, A. demonstrates his often caustic style, but also his approach of deriving his doctrine of Christ from salvation history. A. often defended the language of Nicea, especially in De Decretis Nicaeni Synodi where he writes in favor of the expressions evk th,j ou;siaj and o`moou,siaj. His Epistulae ad Serapion deserve mention as they represent A.’s defense of the Spirit’s divinity and place as the third person in the Trinity. The language he had used to describe the Father and Son, he now used to explain the relationship of the Spirit to the other two persons. While there are other letters and the Tomus ad Antiochenos having to do with proper language concerning the persons of God, the Vita Antonii, was the first life of a saint and became the model of the hagiographical genre. A.’s appreciation of Antony also led to important progress in the relationship between the ecclesial body and monks: the latter came under the jurisdiction of the former.

The central aspect of A’s thought is the God who wants to save mankind. From this concern arises his vehemence in clarifying the ontology of the Son. If the Son is not God, he is not able to save. He did not postulate any degrees of divinity within the Godhead (following OT understandings of the relationship between God and creation). Thus, the Word must either be God or a creature. In defending the (unscriptural) language of o`moou,siaj, A. argued he was preserving the true sense of Scriptural titles for the Son, e.g. Power, Wisdom, Light, etc.

A.’s commitment to the formulation of the Nicene Creed still remains the standard of orthodoxy amongst Christians. It is difficult to overstate the profound affect he has had in the past 16 centuries in theology, each generation having to take stock of his account of the relationship of the Father and the Son based on Scripture.